New Community of Tri-Valley

In addition to its influence on voter participation and support for the school, The Townsman influenced the new perception of a Tri-Valley Community and a new interpretation of local history that was enduring. The historical narrative and vision of community described in The Townsman between 1947 and 1951 became ingrained in the psyche of citizens starting with the second generation to come of age in Tri-Valley who were too young to participate in its creation. Benedict Anderson described how the second generation in imagined communities found it “no longer possible to ‘recapture/The first fine careless rapture’ of their revolutionary predecessors.” Instead of seeing a radical break from the past, they expressed community in a “historical tradition of serial continuity.”[22]

The second generation of the new Tri-Valley community who attended high school between the mid-1950’s and 1960’s accepted the positive vision of the reservoirs, the willing sacrifice narrative of the lost hamlets and the link they had to the creation of Tri-Valley depicted in The Townsman. They also saw reservoir construction as just another chapter in the history of their community. This was apparent in two murals created by the Tri-Valley Art Classes of 1956 and 1957 which were prominently displayed together in the main entrance of the school.

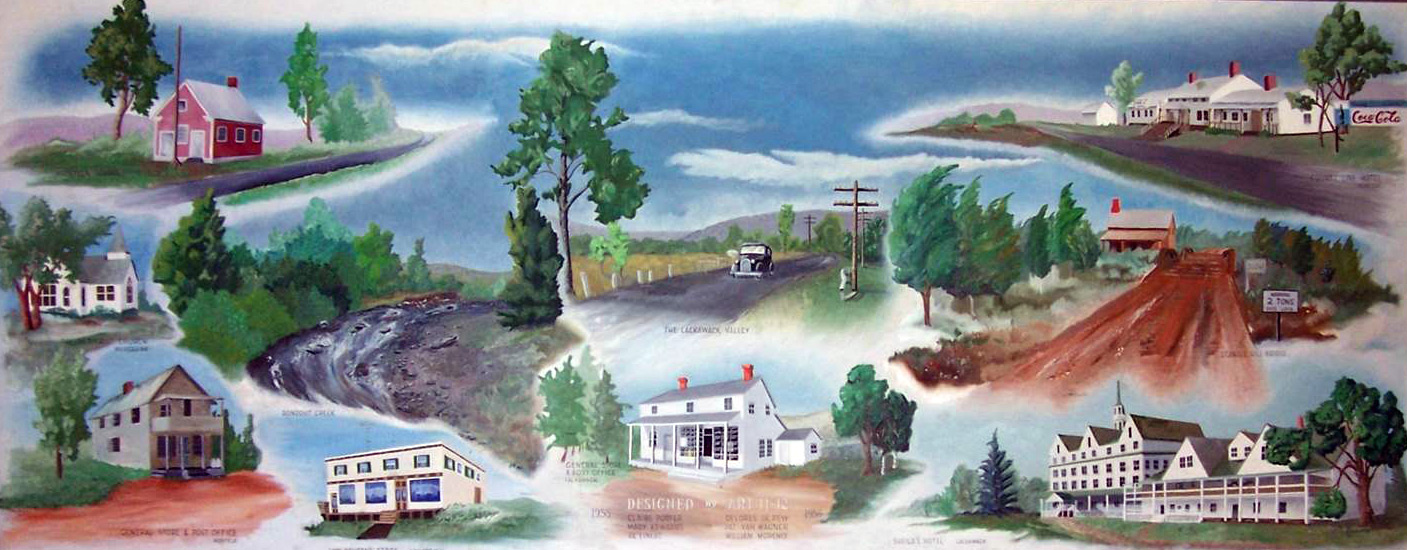

Left: Mural of 5 Lost Hamlets painted by Tri-Valley class of 1956 Right: Mural of Tri-Valley Community painted by Tri-Valley class of 1957.

(Courtesy of Tri-Valley Central School)

In the first mural, students depicted schools, stores, hotels and bridges found in the lost hamlets of Eureka, Montela, Lackawack, Neversink and Bittersweet (See Home Page). They were incorporated into a peaceful rural landscape that emanated a feeling of positive nostalgia.[23] The second mural depicted a single community connected by the reservoirs (See Conclusion). The mural was organized showing the flow of water from the Neversink Reservoir through the hydroelectric plant located in Grahamsville to the Rondout Reservoir.[24] The flow of water continued through pipes bringing water to New York City in the lower corner of the mural. On one side of the reservoirs, the students painted a representation of the Neversink Town Fair. This represented the coming together of individuals from the many different regions of Tri-Valley as well as the continued unique rural character of the community. On the other side, a rural road with woods on one side and a small farm on the other was depicted. This represented the traditional rural past of the area.[25] Taken as a whole, the two murals graphically represented the historical continuity of the community linking the long rural history, “voluntary” sacrifice of the lost hamlets, and reservoir construction with the coming together or consolidation of a single community. The fact that the mural was placed in the school was also telling of the schools centrality to this process.

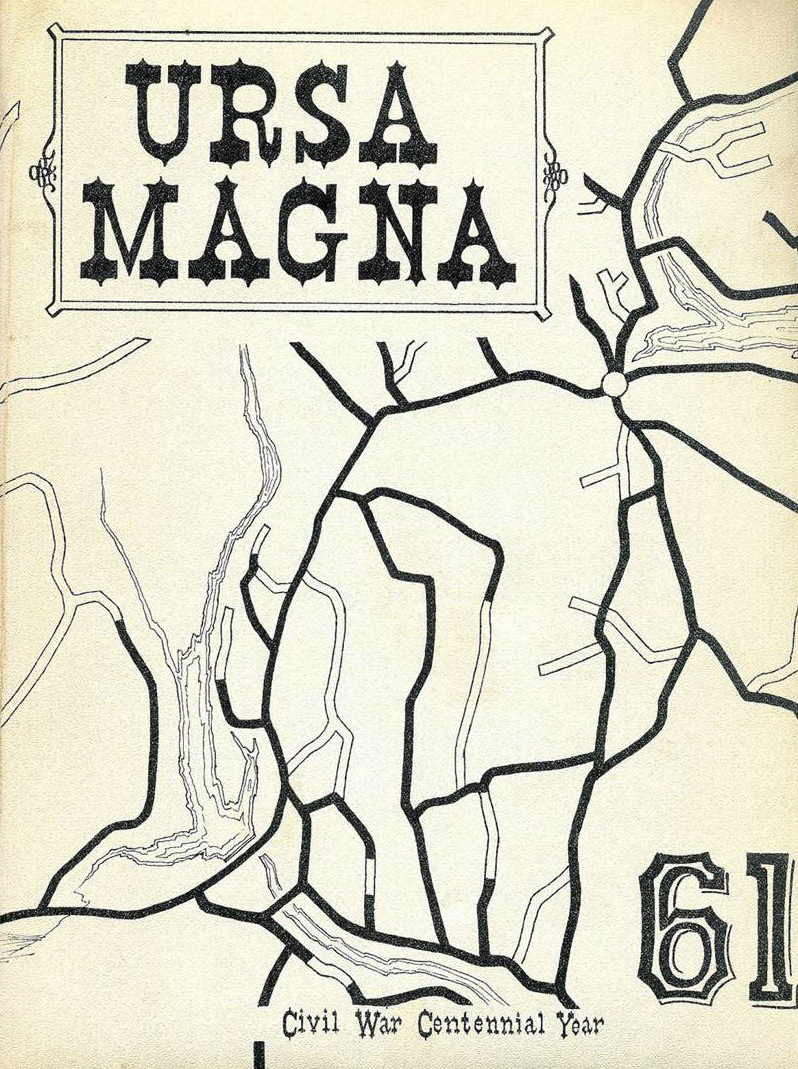

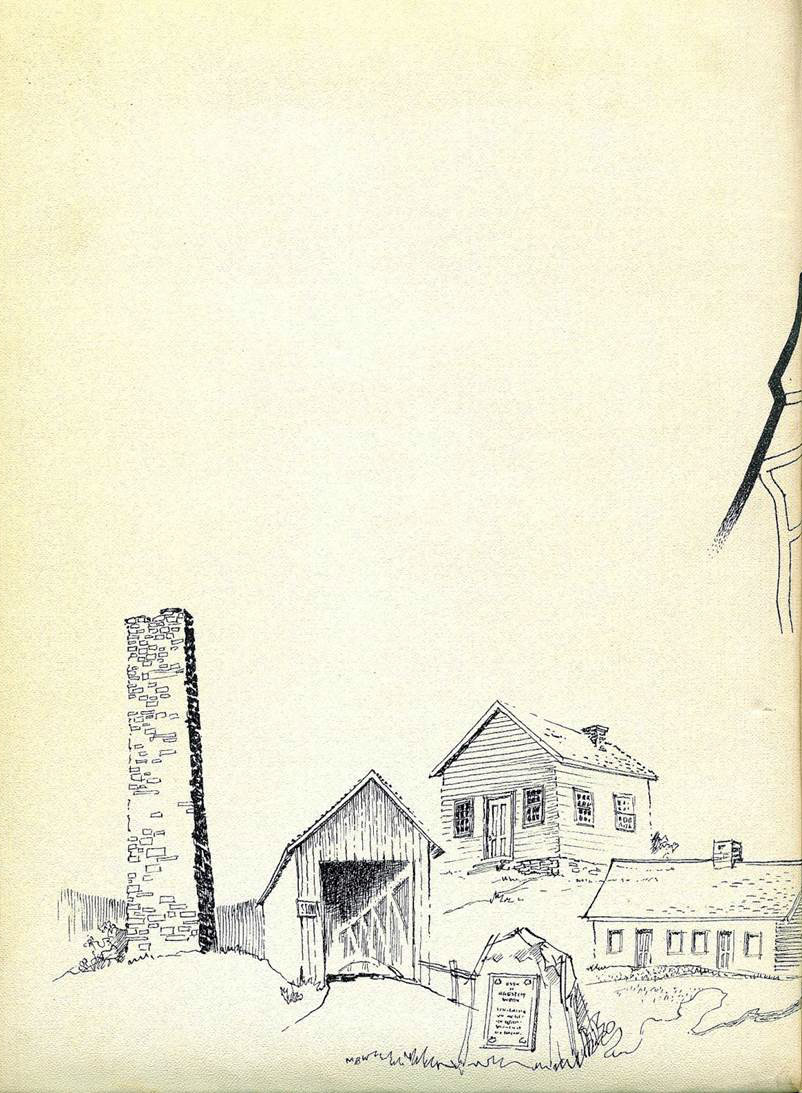

Front and Back Covers of 1961 Tri-Valley Yearbook

Another example of second generation acceptance of The Townsman narrative and perception of the historical continuity of the community was the 1961 Tri-Valley Year Book (See School Consolidation). Because the graduating seniors of 1961 were kindergarteners in 1948 and 3rd graders in 1951, they only had vague recollections of moving into the new school and no firsthand knowledge of the struggle to build the school. Despite this, they were aware that 1961 was the 10th anniversary of the opening of the Tri-Valley Central School and the significance of this anniversary was not lost on the yearbook staff. The front cover of the yearbook was covered with a map of the Tri-Valley Central School District identifiable only by unlabeled sketches of the reservoirs and roads. The roads connecting the community converged on the site of the Tri-Valley school represented by a circle. The back cover of the yearbook was made up of drawings that depicted the Claryville Tannery, Lackawack Hill School, Halls Mills Covered Bridge, Battle of Chestnut Woods Revolutionary War Historic Marker and The Quaker Meeting House.[26] The combination of significant pre-reservoir symbols of the area with depictions of the reservoirs once again suggested the historic continuity and inclusion of the reservoirs in the collective identity of the town. This acceptance of the reservoirs as part of the historical narrative and their use in physically defining the community solidified and legitimized the re-imagining first suggested in The Townsman.

Citations:

22. Anderson, 195. 23. Manville B. Wakefield and 1955-1956 Art Class, Lost Hamlet Mural, 1956, Tri-Valley Central School. 24. The Hydroeclectric plant was built as part of the reservoir project. 25. Manville B. Wakefield and 1956-1957 Art Class, Tri-Valley Community Mural, 1957, Tri-Valley Central School. 26. Ursa Magna: Tri-Valley Central School 1961 Yearbook (Grahamsville: Tri-Valley Central School, 1961).

Daniel Curry

George Mason University

Last Updated 14 May 2014

copyright May 2014